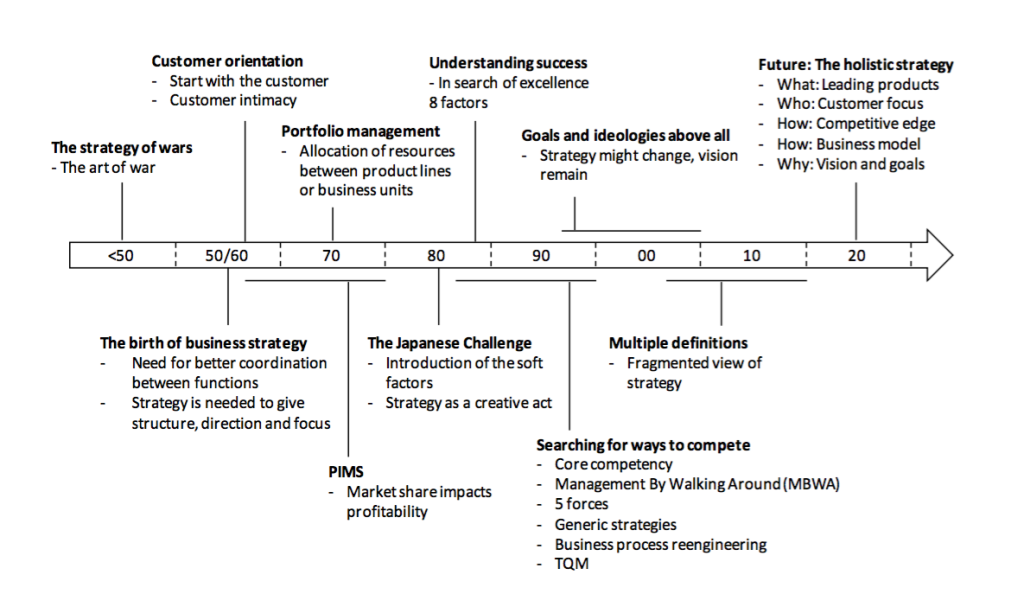

Strategy is not a new phenomenon; it has been around for some time and will likely remain a key concern for business executives as long as competitive markets exist. In this Insight on Strategy, we will take a brief look at the history of strategy to help us understand the context and key concepts. In addition, we will share our own, very personal perspective, on the future of strategy.

It is entirely possible to write long books about the history of strategy, an interesting and broad topic. We will structure this brief article around the key milestones that underlie the development of modern business strategy.

The strategy of wars

Just mentioning the word “strategy” to people may result in them bringing up Sun Zu. He was a successful warrior, but today he is mostly known for authoring “The Art of War,” which is often quoted in strategy-related discussions. Indeed, the earliest references to strategy are typically found in war literature, where strategy is the way to win a battle against your opponents. The most widely referenced piece of work in this area is Sun Zu’s text. “The Art of War” contains many famous quotes that are still widely used, even in the business community:

“Victorious warriors win first and then go to war, while defeated warriors go to war first and then seek to win.”

However, despite historic interest in Sun Zu’s “The Art of War,” it is unfortunately less applicable in today’s business world. While reading the book can be both fun and rewarding, you should not expect many opportunities to apply knowledge from the great Sun Zu directly in your own corporation, unless perhaps you are really fighting to survive.

The birth of business strategy

The natural starting point in understanding the history of modern business strategy is 1950-1960; this period could be considered the birth of business strategy. The key driver behind the formation of strategy was a need to better coordinate company’s activities across different functional units, i.e., a corporate-wide business strategy.

An influential figure during this period was Alfred Chandler; he stressed the importance of taking a long-term perspective when planning for the future. In 1962, Chandler released “Strategy and Structure: Chapters in the History of the Industrial Enterprise,” which posited that a long-term strategy was necessary to give a company structure, direction, and focus.

Other key influencers in this period included Philip Selznick, Igor Ansoff, and Peter Drucker. In particular, Peter Drucker was an amazingly productive writer who released a dozen management books that helped push the development of strategy forward. Drucker stressed the importance for an organization to have an objective and to steer and follow-up on that objective throughout the whole organization.

Customer orientation

The original idea from capitalism was that customers will come if a company produces good products. This worked very well in an undersupplied market until the post World War II when demand actually was satisfied. The 1950s and 60s marked a time when companies started to focus on sales as a lever to drive demand for their product and services.

Theodore Levitt was especially important in this field; he provided a new perspective on how sales should be executed. He claimed that rather than developing a product and then trying to sell it, companies should start with the customer and try to understand their fundamental need. The customer should then become the driving force for everything that the company does. This is still the line of thinking that management discussions refer to as customer intimacy or customer orientation.

PIMS

The next major landmark in the development of strategy was PIMS (Profit Impact of Marketing Strategy). PIMS was a study initiated in the 1960s by Sidney Schoeffler at General Electric. The key question was to determine why some business units were performing better than others based on empirical evidence. While this study originally began as an initiative to understand the differences between different strategic business units within GE, it was later expanded to cover a broader scope of companies. Harvard University took over the study and ran it between 1972 and 1974. Since 1975, PIMS has been run by the Strategic Planning Institute (SPI), a non-profit organization established with the objective to maintain and develop the study.

Some significant findings have been drawn from the study; perhaps one of the most important was the strong correlation found between market share and profitability. Conclusions from the PIMS study have not been without criticism. Some people argue that results might be skewed because company selection is biased toward larger companies that typically operate in more traditional industries. Even more interesting is the criticism that claims that the study did not sufficiently clarify cause and effect. Perhaps large market share did not drive high profitability; rather, large profitability could have allowed companies to make investment that made them more competitive and gave them a leading position in terms of market share.

Portfolio management

The next step in the evolution toward modern business strategy practice was the evolution of portfolio management theories. This evolution clearly follows key findings from the PIMS study. The most famous of these theories and frameworks is the growth-share matrix developed by Bruce D. Henderson and the Boston Consulting Group in 1970.

The purpose of the growth-share matrix was to serve as a framework to be used when allocating scarce resources between different business units or coexisting product lines in the same company or group.

By assessing relative market share and market growth of business units or product lines, four different categories are established. “Cash cows” generate cash in excess, but they do not necessarily grow significantly in the market. “Dogs” are business units or product lines that do not grow in the market and where the company doesn’t have a high relative market share. “Question marks” are product lines or business units with potential. Market growth is significant, but the company doesn’t have a high relative market share. Finally, we have the “stars,” which are product or business units with high market growth where the company has a high relative market share.

“To be successful, a company should have a portfolio of products with different growth rates and different market shares. The portfolio composition is a function of the balance between cash flows. High growth products require cash inputs to grow. Low growth products should generate excess cash. Both kinds are needed simultaneously.”—Bruce Henderson (Henderson, Bruce. “The Product Portfolio.”)

The Japanese Challenge

In late 1970s, it became apparent that Japanese companies were surpassing American and European companies. This happened in many different industries such as steel, watches, shipbuilding, electronics, cameras, autos, and others. This marks the next important step in the evolution of business strategy focused on assessing the root causes of this development.

Many theories attempted to explain the differences, and one of the more important ones was published in 1981 by Richard Pascale and Anthony Athos in their book “The Art of Japanese Management.” They claimed that management could be divided into seven different domains: Strategy, Structure, Systems, Skills, Staff, Style, and Supraordinate goals. The first three domains were considered the hard domains and the remaining four were the soft domains. They concluded that American companies were particularly good at delivering on the hard domains while paying little or no attention to the soft domains. Conversely, contemporary Japanese management had fully embraced the four soft domains, and Pascale and Athos concluded that this explained their superiority at the time.

Another explanation for the differences was provided by Kenichi Ohmae, who was heading up McKinsey & Co’s Tokyo office. He claimed that American companies applied an overly analytical approach to strategy development, while Japanese companies were better positioned to see strategy development as a creative act.

Understanding success

In 1982, Tom Peters and Robert Waterman released a study that also pertained to the Japanese Challenge. They examined a large number companies to try to find the common traits among the successful ones. “In Search of Excellence” finally listed eight traits that they found in all of the successful companies they studied.

- Action orientation: Do it, try it. Don’t waste too much time in planning.

- Focus on customer: Know and understand your customer.

- Entrepreneurship: Give people in the organization a mandate to act. Even large companies should be able to think and act small.

- Focus on people: Treat people well, and you will get productivity and results in return.

- Focus on values: The CEO should focus on communicating and living the corporate values.

- Stick to the core: Do what you know well.

- Simple and lean: Complexity just creates confusion and increases waste.

- Centralized and decentralized at the same time: Centralized control with decentralized autonomy.

Searching for ways to compete (1980-1990)

Following the Japanese Challenge, the next phase of the development of business strategy involved a broad search to find viable ways to compete. There were several different theories presented, and all together this provided a broad palette for business managers to choose from.

C.K. Prahalad and Gary Hamel claimed that every company should recognize the one or two things they do better than other companies, and that is their competitive advantage. They called this “core competency.”

“A company’s competitiveness derives from its core competencies and core products (the tangible results of core competencies). Core competence is the collective learning in the organization, especially the capacity to coordinate diverse production skills and integrate streams of technologies.” C.K. Prahalad and Gary Hamel

Dave Packard and Bill Hewlett at HP claimed that strategy should be developed based on a fundamental understanding of the business and close contact with customer, suppliers, and employees. They called it “Management By Walking Around.”

The most influential strategist of this period was Michel Porter, who provided many different frameworks for identifying competitive advantages, many of which are still used. Porter’s Five Forces model was a framework specifically designed to analyze and understand the competitive environment in which a company operates. Porter also introduced generic strategies by which he claims that any company can choose among three different ways of competing: overall cost leadership, differentiation, and focus.

Michael Hammer and James Champy claimed that competitive advantage could be derived from a superior end-to-end process. The idea was to organize the firm’s assets around key business processes rather than functional silos. The theory was popularized under the term BPR (Business Process Reengineering).

The above-listed theories simply represent a sample of ideas brought forward during this period of time; the list could be made longer by adding Best Practices by Richard Lester and Total Quality Management (TQM) by W. Edwards Deming, among others.

Goals and ideologies above all

The period after the great search for competitive advantage involves a much greater emphasis on an organization’s purpose and objective. This period began at the end of 1990 and continues into the 21st century.

James Collins and Jerry Porras spent 6 years examining empirical studies to identify fundamental factors that distinguish great companies. They found that while strategy and tactics might change, the companies that continuously win have a firm core set of values. They published “Built to Last” in 1994 and claimed that in the long term, employees are motivated by fundamental ideology but not short-term competitiveness and/or profits.

“Visionary companies pursue a cluster of objectives, of which making money is only one—and not necessarily the primary one.” Collins/Porras “Built to Last”

James Collins also popularized the term BHAG: Big Hairy Audacious Goals. It refers to ambitious goals, beyond financials, that will motivate employees for long-term engagement.

The dot-com bubble was starting to build at the end of 1990s; it finally burst on March 10, 2000. During this time, many of the fast-growing companies shared the same motto: “Get large or get lost.” Few of the companies were concerned about the financials, and making losses was not an issue. The key focus was growth, in particular customer growth. Remember, this was the time when not even Google was making a profit, but it was investing heavily to grow. Everybody was talking about the “new economy,” which implied a totally new paradigm in contrast to the “old economy” that focused on fundamental financial measurements.

Goals and ideologies mattered in the new economy, which was in line with the thinking from individuals like James Collins. But strategy beyond goals and ideologies was not a widely discussed topic. In fact, many claimed that due to the rapid changes, strategy was not worth the effort or could not be defined at all. This period is what we refer to as the strategy “low-point.” Fortunately, things have improved since then.

The future of strategy

We currently operate in a period where there are multiple definitions of strategy. Ask your colleagues to define strategy, and you will get as many answers as questions. You will typically notice that competitiveness has a clear position in the definition, but strategy can also be defined as a plan for realizing a vision or goals.

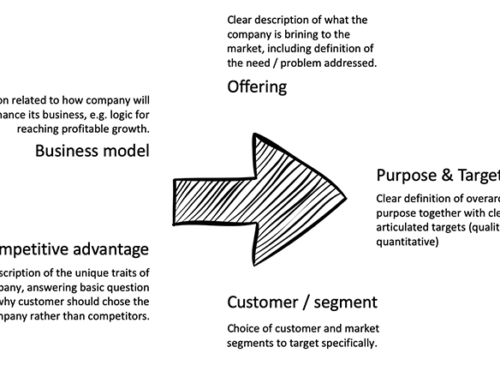

What about the future of strategy? Our perspective is that we will take a more holistic perspective that will build on the existing theories from the history of strategy.

In the future, we discuss a holistic strategy that driven by product leadership (the leading paradigm before World War II), enables customer focus (as addressed in the 1950s and 60s), and incorporates the issue of competitiveness (explored in the 1980s and 90s by Porter and others). The holistic strategy will bring all of these components together with the overarching goals and objectives of the company as described by Collins and others.

The holistic strategy as described here is fundamentally a mash-up from the history of strategy. This way of looking at strategy is fundamentally what we practice and promote at 2by2. Strategy is not going away; there is no contradiction between today’s business needs and having a well thought out business strategy. The need for a more holistic business strategy is here to stay.

The holistic strategy, a mash-up from history, should answer several key questions:

- What are your overarching objectives and goals? (Collins et al)

- What do you bring to the market? (products/services) (pre World War II)

- To whom are you offering your products and services, and what fundamental need are you dressing? (Levitt et al)

- Why should the customer choose your product or services instead of the competitors; what is your competitive advantage? (Porter et al)

- How are you going to earn money; what is your business model? (PIMS and learning from the dot-com bubble)

References

- Zu, Sun: “The Art of War”

- Chandler, Alfred: “Strategy and Structure: Chapters in the history of industrial enterprise”, Doubleday, New York, 1962

- Drucker, Peter: “The Practice of Management”, Harper and Row, New York, 1954.

- Henderson, Bruce: “The Product Portfolio”. Retrieved 3 April 2013

- Pascale, R. and Athos, A:. “The Art of Japanese Management”, Penguin, London, 1981

- Ohmae, K.: “The Mind of the Strategist”, McGraw Hill, New York, 1982.

- Peters, T. and Waterman, R.: “In Search of Excellence”, HarperCollins, New York, 1982.

- Hamel, G. & Prahalad, C.K.: “The Core Competence of the Corporation”, Harvard Business Review, May–June 1990.

- Hammer, M. and Champy, J.: “Reengineering the Corporation”, Harper Business, New York 1993.

- Porter, M.E.: “Competitive Strategy”, Free Press, New York, 1980

- Porter, M.E.: “Competitive Advantage”, Free Press, New York, 1985

- Collins, James and Porras, Jerry: “Built to Last”, Harper Books, New York, 1994

[…] […]